Astana, the start of my 3380 km (2100-mile) adventure through Central Asia, is not a place most people would elect to visit. Largely devoid of history, monuments of note, and even semi-interesting topography, Astana has very little to offer relative to the many storied Silk Route towns and cities spread across the various Stans. It was certainly not my first choice of city to embark on such an endeavor from, but looking back, I’m more than glad I did.

Formerly known as Nur Sultan, and the present day capital of Kazakhstan, Astana is located in the north of the country, within a flat, semi-arid steppe. Astana strikes one as a very modern city at first, with a certain degree of Middle East envy. Architecturally, that translates to everything from the whimsical to the bizarre, with some internationally acclaimed talent thrown into the mix. But while Astana’s mostly futuristic aesthetic may not appeal to everyone, it is the sheer thought put into the layout and planning of the city that is hard to ignore. The parks, the landscaping, the riverfront, the generously sized boulevards, the integration of walking and biking into the streetscape – the Kazakhs have spared no effort in making Astana an incredibly pleasant city to wander through. They started with a blank canvas, sure, but like too many cities I know, didn’t squander that opportunity. And they did so for a city that has one of the most short-lived summers on the planet. I was mighty impressed.

The dining car on Train 4 was packed by the time I got there, but recognizing my distress, a helpful waitress ushered me towards the one seat that lay unoccupied across from a burly Kazakh gent. The language barrier was hard to overcome, what with the absence of cellular coverage and a Wi-Fi network that refused to work, but the man was welcoming, and in no time we were sharing peanuts, samsas, and clinking our glasses of nicely chilled Zhiguli. The Kazakh dining cars, much like their Russian counterparts, offer a cheery environment, remain open late, and almost never reopen on time for breakfast.

Like many other institutions of note, the Kazakhs inherited their railways from Russia, which meant the country was perfectly set up for overnight sleeper travel. And while Soviet-era carriages still account for much of the Kazakh railway fleet, Spanish company, Talgo, has been the manufacturer of choice in recent years, gradually taking over the haulage of passengers on overnight trains. Having ridden Talgos in other geographies previously, I kind of knew what to expect, but the Kazakhs had taken it to a whole new level. The interiors were spick and span, the crew was very smartly turned out, and everything looked and felt like it was factory-fresh, even though the trains have been in production domestically for over a decade now.

Beginning my third full day in the country, I was nowhere close to overcoming jetlag, and that proved rather beneficial. Be it stepping out into the crisp morning air of Sary Shagan, our first station stop come daybreak (0430, to be precise), or viewing the humongous expanse of Lake Balkhash from the corridor of my carriage – unhindered by my fellow passengers, who were yet to emerge from their slumber. My own sleep – the few hours that I got – had been unabashedly interrupted in the middle of the night by an elderly lady, who didn’t mask her displeasure at the fact that I had locked the cabin from within. She claimed her upper bunk amidst all the chaos, and didn’t surface till we drew closer to Almaty, by which time she had considerably warmed up to me.

Not wanting to disturb her, I flitted between the corridor of my carriage and the dining car, utilizing multiple points of vantage, indulging in a breakfast of yogurt-filled blinis and several servings of strong Americano, and staring out at the vastness of the Kazakh Steppe; the largest dry steppe region on earth, covering a staggering 804,450 sq km. Ever so gently, the landscape changed to rolling hills, and eventually, loftier mountains. We pulled in to Almaty on the dot.

The queue for the Köktöbe cable car was long but fast moving. Once up there, the views made it all worth while, and gave one an instant appreciation for the fabulous setting of Almaty, the former capital of Kazakhstan. Nestled in the shadow of the Altai Mountains, come winter, Almaty becomes the de facto gateway for all activities winter related. But it’s during the warmer months that the city is, possibly, more of a crowd pleaser. When its flower beds are in full bloom, its thoroughfares are thriving, revelers cram its streets till the wee hours, and the lines for said cable car never seem to end.

The first thing that strikes you about Almaty is just how green it is. Parks are everywhere. From the higher reaches of Köktöbe to those converted from state-run apple orchards. One dedicated specifically to Mahatma Gandhi, to another coincidentally named after Manhattan’s centerpiece. All of them built with the same intent – for kids to have a jolly time. Adding to that, a recent effort in the city center to reclaim streets from cars, and actually designate them “walking streets” has already paid rich dividends. The European-style pedestrian forward thoroughfares have contributed to a robust cafe culture, a vibrant collection of street art and murals, eateries that run the gamut and often stay open through the night, and streets that are well illuminated and safe to walk through at any time. Almaty has gained plenty from its Soviet past too. An influence that extends into the city’s many imposing government edifices, grand military monuments, impressive onion dome cathedrals, a legacy of trolley buses, and an efficiently-run metro. It’s a city that will grow on you very quickly, and make you want to return, no matter what season you choose to visit in.

Barring the fact that the carriage orientation was different, and that I had the cabin entirely to myself, the rest of the set up for Train 1 was largely the same. Another impeccably well kept Talgo set, with a well-stocked dining car, and Wi-Fi that refused to work. Sunrise, a little past 5 am, was one of the most spectacular sights I’ve witnessed from a moving train. We were riding high along an embankment in the country’s Turkestan region, following the contours of the land, where the western spur of the Tian Shan Mountains straddles the border between Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. There was no chance of snoozing once I had lifted that blind.

The crossing of the Aksu River was followed by a brief halt at Mankent, and another longer one at Shymkent, the third largest city in Kazakhstan. By the time the dining car reopened for business, we were pulling into Arys; its large marshaling yard no coincidence, given its location at the junction of two important rail lines, the Trans-Aral Railway and the Turkestan-Siberia Railway. For breakfast, more blinis – meat-filled this time – were ordered, along with a generous serving of tea.

Minutes after arriving at Saryagash, the Kazakh border station, an off-leash K9 did the rounds of our carriage; his handlers, and a handful of Kazakh border control officers, following suit. One of them, profusely sweating, entered my cabin and inspected my passport, and a few minutes later, stamped me an exit seal. Cellular coverage dropped as soon as we crossed the heavily fortified border into Uzbekistan. At Keles, on the Uzbek side, my passport was collected by an officer, and another came by to check my bag and ask a few basic questions. My luggage was photographed by yet another gent, and the last round of inspections were carried out by a panting stunner of a German Shepherd, once again unsupervised. The formalities at the Uzbek border took a lot longer than expected, which resulted in a slightly late arrival into Toshkent Vokzal.

Tashkent was a lot warmer than it should’ve been in July – breaching the 40°C (104 F) mark while I was there – but that didn’t seem to deter its population from being out and about. Even before sunset, misters were switched on en masse, and the whole city emerged into the open, claiming the outdoors for the night. Despite the presence of air conditioning everywhere, the locals seemed to prefer sitting along sidewalks and at restaurant patios, taking in the sights. An oddity at first, this would be a recurring theme during my time in the country, and eventually, I joined in too. At one such al fresco establishment, I got my first taste of Uzbek cuisine in the form of plov. It took a bit but eventually that realization dawned – India’s own cuisine owed much of its existence to this part of the world.

Rebuilt to be a model city following the devastating earthquake of 1966, Tashkent benefited immensely from Soviet urban planning. At the time, it was the fourth largest city in the Soviet Union, behind Moscow, St.Petersburg and Kiev, and much like they had with those cities, the Soviets put their best foot forward. Today, Tashkent appears as a contemporary and cosmopolitan city, seamlessly blending rich history with its standing as a financial and commercial hub, not just in Uzbekistan, but also in Central Asia. There were many things to admire about the city, but my absolute favorite remained the Tashkent Metro. Fifty unique stations, each embellished with bas-reliefs, tiled murals, wall mosaics, ornate columns, and lavish light fixtures. At 14 cents a ride, perhaps the most inexpensive museum in the world.

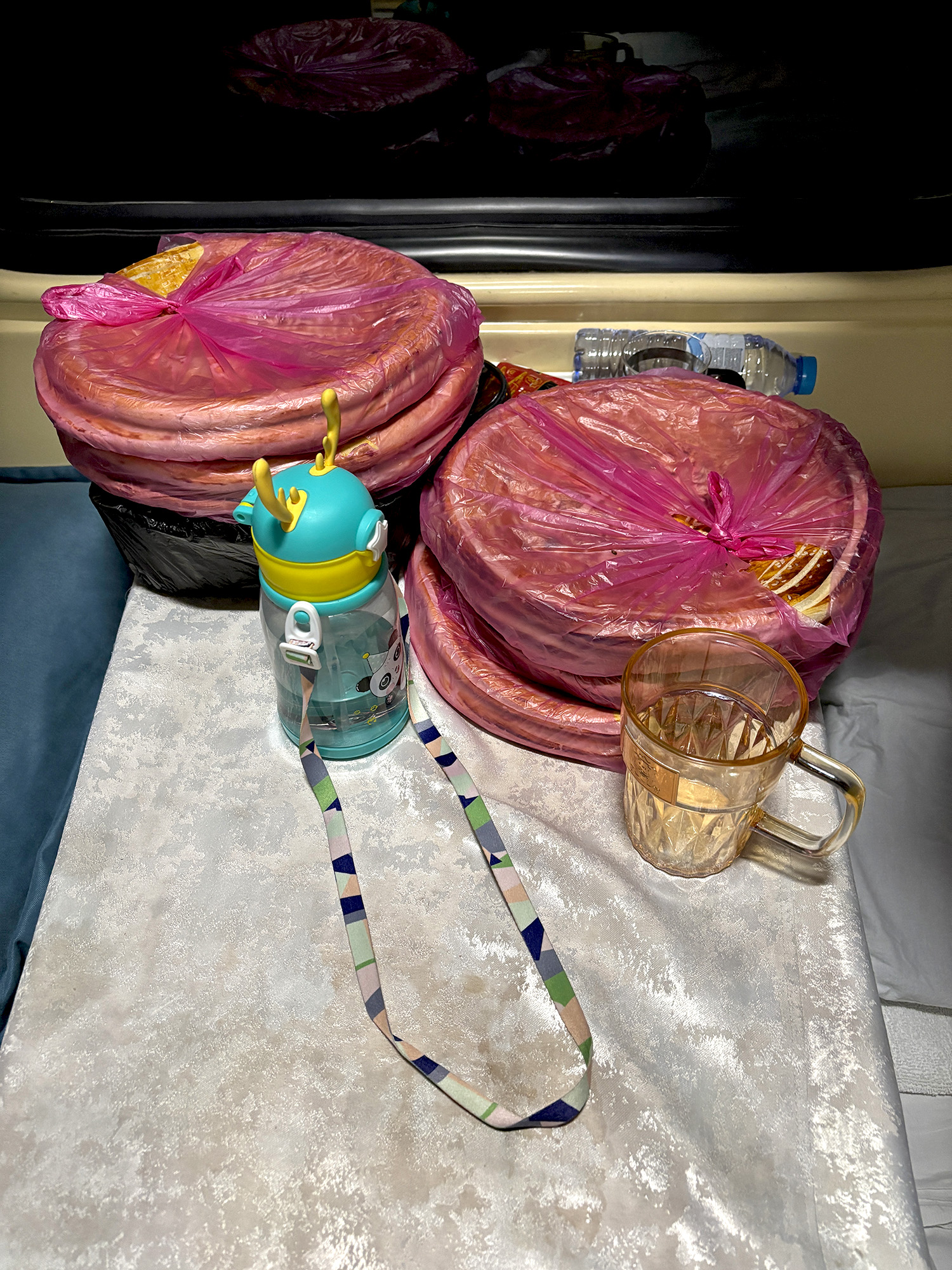

Toshkent Janubiy, also known as Tashkent South or Yuzhny Vokzal, is the second of two main stations in the city, and my train to Bukhara departed from there. The distance to Bukhara could easily have been covered by a much faster day train, but I specifically chose an overnight sleeper for the journey. It was a Soviet-style train, to begin with; the type I’ve spent several nights on in the past, so there was a bit of nostalgia involved. Second, and more importantly, I was glad to finally take a break from that rather annoying staccato beat that the single-axle Talgo carriages produce. What I hadn’t bargained for though was a claustrophobic cabin. No fault of the matriarch and her family who were carrying far too much luggage, but because the air con only kicked in once the train started moving – the carriage was that old! On the plus side, the cabin had the aroma of fresh baked non, of which the lady was carrying enough to feed the entire train.

I must have knocked off not long after we pulled out of Toshkent Janubiy, only arising as Train 125 was racing along the west face of Lake Tudakul, with the AM light working its magic. It was an early arrival at Bukhara, which meant a banana and a cup of tea were in order. Despite the significant inroads coffee has made in recent years, tea is still big in this part of the world, and the Uzbeks still serve it in proper glassware. I watched as other travelers stepped off the train to imbibe theirs around communal stands, set out by the station cafe, then hurry back to reboard the train as the station bell was rung. As the train departed towards Khiva, I set off to explore Bukhara.

Integral to the Silk Road, the city of Bukhara has existed for almost three thousand years. On the longish drive from the station though, you could be forgiven for believing you had alighted elsewhere. An endless sea of construction lined the road, as if a small town from the Soviet-era had been given the mandate to expand rapidly and modernize. Thankfully, the city center of Bukhara couldn’t have been more different. There was ongoing construction there too, but for very different reasons. Plazas being repaved, pedestrian access being expanded, and monuments being renovated. And while a lot of it was being done to attract more visitors, and further cement its status as a World Heritage Site, the historic heart of Bukhara is still very much lived in. Cutting through the center en route to their places of work, going about their daily chores, partaking of the shade at the many public squares, and emerging in droves come sundown, locals easily outnumbered tourists while I was there.

Relative to the other stops I was making on this trip, Bukhara was decidedly compact, with several of its landmarks easily covered within a day. But a handful of sights left enough of an impression to lure me back the next day. The Bolo Hauz Mosque with its handsomely painted wooden columns. The magnificent Poi-i-Kalan ensemble – by day, and even more so by night. Wandering through the arched passageways of Bukhara’s ancient trading posts or toqis, and staring at the oldest preserved madrassah in Central Asia, through the exquisite portal of another. At the last of these, the Abdulaziz Khan Madrassah, I was befriended by Mimin. A vendor at the monument, Mimin approached me, and separately, another visitor, with the offer of a home-cooked meal that evening. He lived a short walk away, he claimed. For most of that day, I grappled with the obvious element of apprehension, but eventually caved in. Hours later, fellow tourist and I left Mimin’s house thoroughly satiated, both very glad for not having turned down his offer.

Afrasiyab is an ancient archeological site in Samarkand, the city I was headed to next. And my train for that leg – another Talgo this time – was named for it. The Afrosiyob-branded trains are Uzbekistan’s high-speed day trains, which have, since their introduction in 2011, cut down travel times between Tashkent and Bukhara by half. The day-time configuration of the carriages on Train 767 meant there was no dining car to while away the time in, so I had to make do with my plush business class seat, with very generous leg room, and a recliner that I couldn’t coerce into working. The train was well appointed and extremely comfortable, and the higher speeds meant that the irregular beat of the Talgo was largely masked. It was flat as a pancake outside, and nondescript save for occasional tracts of agricultural land. Two quick halts at Navoiy and Kattaqo’rg’on, and before I knew it, we were pulling into Samarkand.

Along with Bukhara, Samarkand is one of the oldest continuously inhabited places in Central Asia. From the rule of Alexander the Great to its sacking by Genghis Khan, from the height of the Persian and Turkic empires to the glory of the Tamerlane-era, its incredibly rich history is most beautifully illustrated through the daily son et lumière at Registan Square. It’s free, and you don’t want to miss it. It’s the very square where Timur‘s grandson, Ulugh Beg, built a madrassah in the early 15th-century, and where two more centers of learning cropped up not long after. A great place to start one’s exploration of the city, the Registan ensemble could possibly be considered the piece de resistance of Samarkand, but as I quickly discovered, there was a lot more to this multi-faceted city.

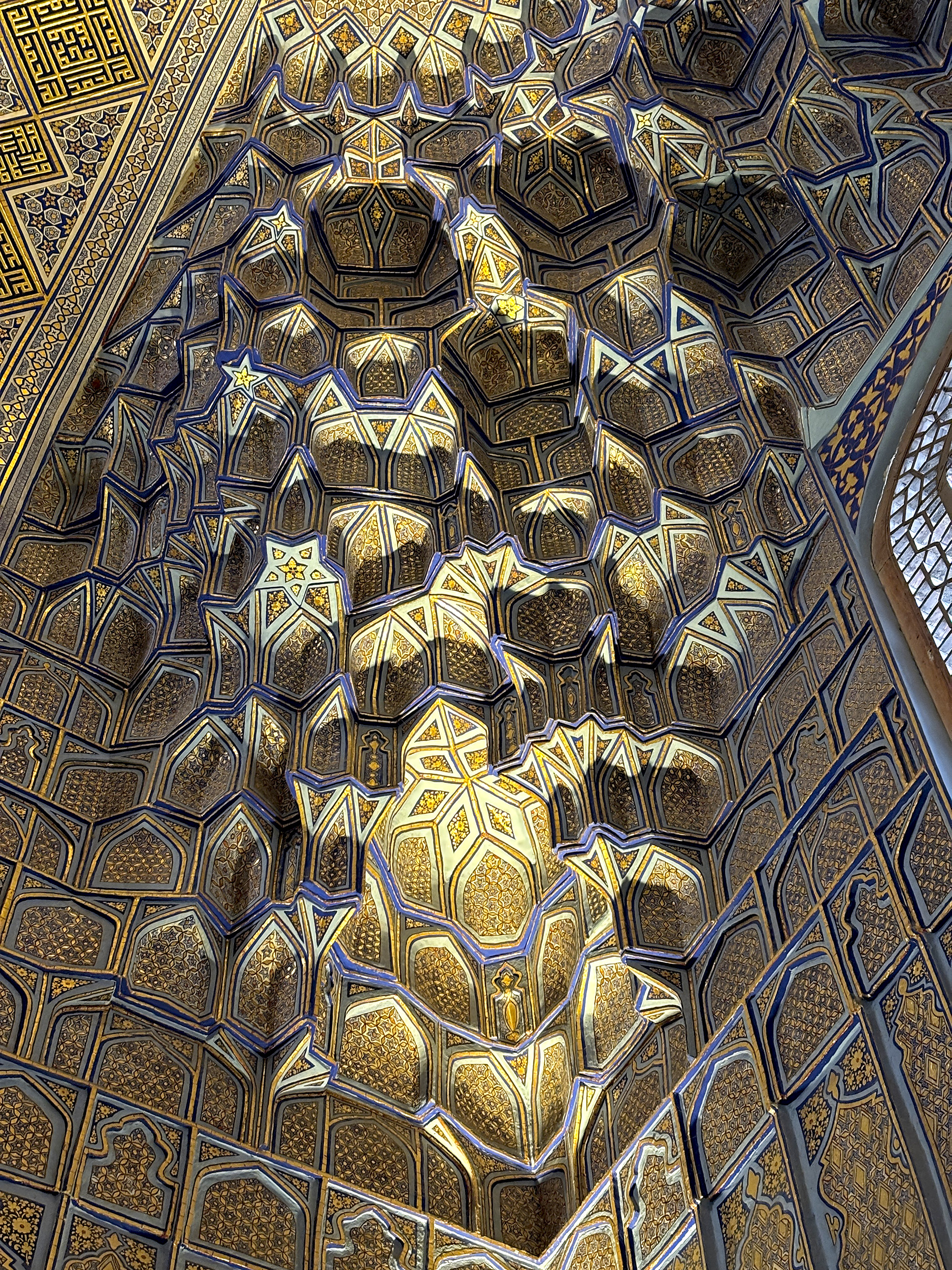

An early morning visit to the the Gur-e-Amir mausoleum, where Timur was laid to rest in 1405, paid rich dividends. I beat the heat and the crowds, and had the exquisite interior – adorned with fabulously intricate muqarna decorations – to gape at, all by myself. There was no avoiding the crowds at Siyob Bozori though; a covered wholesale market that sits in the shadow of the imposing Bibi-Khanym Mosque. Where larger-than-life watermelons and succulent melons lined the narrow alleys, and a much thicker variant of the national staple, Samarkand non, vied for attention. Where the words bozori, do’kon and go’sht had me wondering about the etymology of similar words with precisely the same meaning in India. Where the chaos outside to catch a bus also reminded me of home. I hopped on one of those buses and headed north.

Sultan, mathematician, and perhaps one of the greatest astronomers of his time, Ulugh Beg built an observatory north of Samarkand in the 1420s. It was tragically destroyed by his own son in 1449, only to be rediscovered in the early 20th-century by Russian archeologist, Vassily Vyatkin. The remains of his observatory, and a museum dedicated to it won’t take up much of your time, but they offer vital testimony to an age aptly referred to as the Timurid Renaissance. A short bus ride from there, lying halfway between the observatory and the city center is the Shah-i-Zinda or “the living king” ensemble, a gobsmackingly beautiful collection of Timurid-era mausoleums, spanning twenty structures built over eight centuries, all painstakingly restored. That collection alone, in my humble opinion, is probably worthwhile going all the way to Samarkand for. The long day ended with me back at Registan Square. So brilliant was the sound and light show the previous night, I couldn’t help but watch it again.

Train 711 for Tashkent was a “Sharq” service. A slightly slower alternative to the Afrosiyob, featuring Soviet-era seating cars, and to my pleasant surprise, a dining car too. There was lots to look forward to on my final train journey through Central Asia, but as we pulled out of the station, I couldn’t help but feel as if I was leaving something precious behind. It was the tail end of my trip, and Samarkand had my heart. I had inadvertently saved the best for last.

A full set of photos from my train journeys, and my time in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan can be seen on my Flickr.

Wow Brat! I really feel like I did this journey with you… beautiful post and photos. Every time I read these love letters to places far-flung, it reignites the wanderlust in me! Thank you for sharing.

Truly inspirational. Now I feel I should visit these fabled cities too.A very smooth flow of writing. Keep it up. BTW, India also uses the word registan referring probably to sandy arid lands, or even a desert.